A Guide to Choosing Hybrid Power Solutions for Your Needs

Hybrid power today has become a practical response to rising energy costs, grid instability, and growing reliability requirements. A hybrid power system combines multiple energy sources-often renewables, storage, and conventional generation-into a coordinated whole. When designed correctly, a hybrid power solution does more than reduce fuel use; it changes how energy risks are managed.

Choosing the right system requires more than technology selection, it requires clarity about objectives, operating conditions, and system behavior over time.

What is a Hybrid Power System?

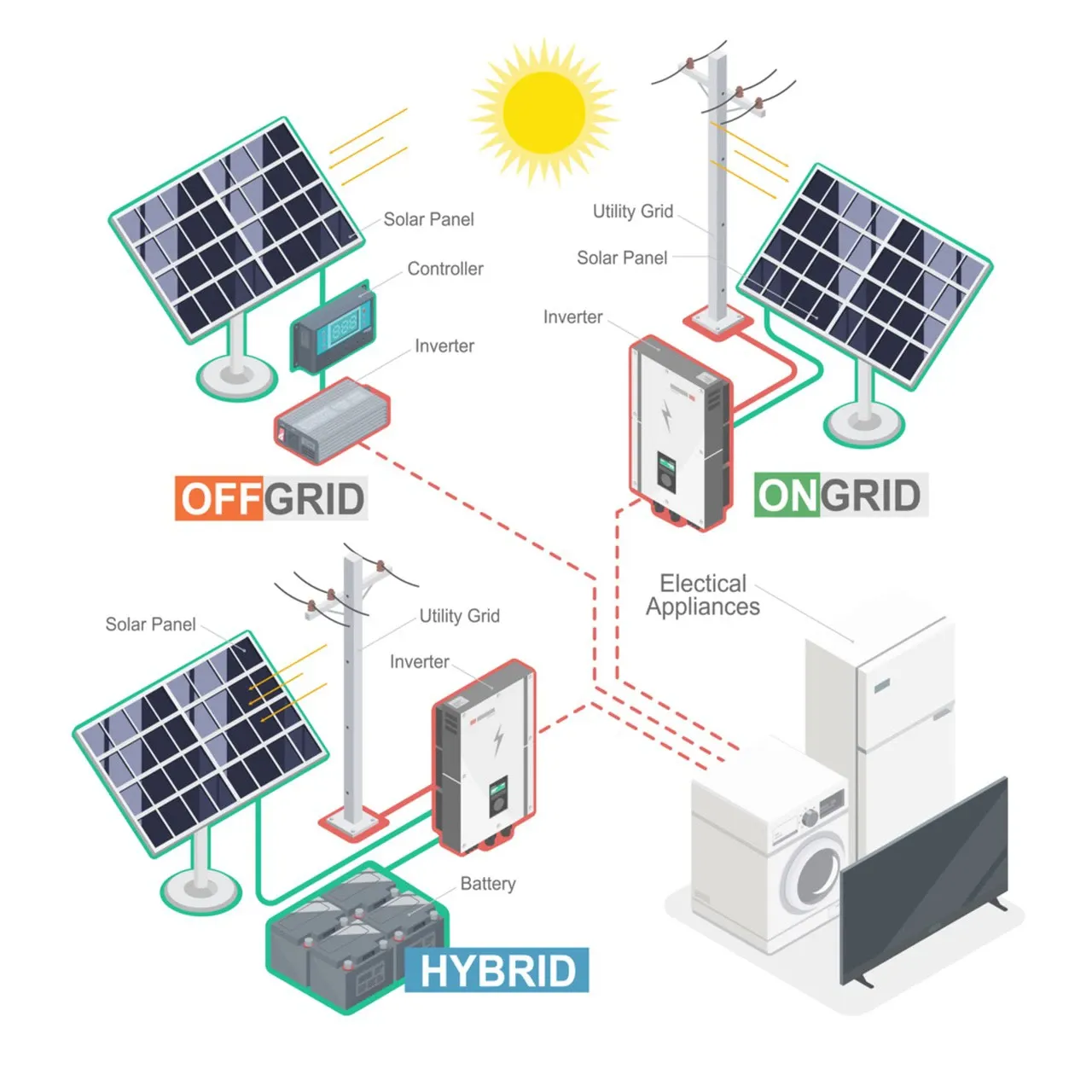

Hybrid power is a concept that’s often perceived as nothing more than “renewables plus batteries”. The truth, though, is that a hybrid power system is actually defined through integration and control. There needs to be a set of multiples of energy assets working under one clear strategy within dynamic responses to load changes, resource availability, and even disruptions.

Many technologies comprise a system, but without coordinated control, it’s not truly a hybrid. The control logic—how and when each resource is dispatched—turns components into a system.

Why Hybrid Power Is Gaining Favor

Organizations choose hybrid power solutions for various motivations. However, there always seem to be three underlying motivations for such adoption. These include cost management, resiliency, and the ability to operate. When it comes to the challenges faced by different power solutions, power solutions dependent on fuel always have the challenge of fluctuating costs. On the other hand, power

The study titled Hybrid Power Plants for Energy Resilience: A Case Study, published by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory illustrates how hybrid power plants can improve resilience by using generation and storage capacities during a grid outage to decrease reliance on a single source of energy while keeping essential loads functional.

This resilience advantage underlines the rising adoption of hybrid power in critical infrastructure, remote sites, and heavy industry applications.

Begin with the primary objective, rather than the technology itself

The most common pitfalls of a hybrid power project include the possibility of beginning with technology selection rather than beginning with the goals of the system. What looks optimal for a given goal regarding fuel savings would be completely different for another goal like availability.

If it is cost reduction, system designs will emphasize renewable energy penetrations and efficient use of storage. If resilience is the aim, then redundancy and rapid response and operational reserves may have to improve and at the expense of increased fuel use.

Cost, Reliability, and Complexity

A common pitfall is trying to optimize for each benefit at the same time. The more technologies being integrated, the more difficult the control will be. By establishing priorities, the final system can be kept to what is really valued.

Control strategy is at the core of system performance.

The control architecture plays a major role in determining the real-world outcome in hybrid power systems. Advanced controllers give the command for charging/discharging of storage, dispatch of generator, and response to faults or sudden changes in load.

According to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s publication Opportunities for Research and Development of Hybrid Power Plants, coordinated control and system-level optimization are central in realizing the full economic and operational value of hybrid configurations, especially as systems integrate more diverse resources.

Are blood cells destroyed by the bile salts found in the bile? This is the important point: hybrid power is a systems engineering challenge, not a component-matching exercise.

Site conditions really shape any hybrid power solution

No hybrid power system can be designed in isolation from its environment. Resource availability, climate conditions, fuel logistics, grid quality, and regulatory constraints all influence feasible designs.

For the remote sites, the priorities are fuel reduction and autonomy, while peak shaving or backup power is considered for grid-connected sites. Thus, technology selection can also be influenced by such environmental factors as temperature extremes or dust, besides affecting enclosure design.

Load Profiles Are More Important Than Installed Capacity

Peak demand figures are useful, but often, it is the variability of the load that matters more. The more stable and predictable a load is, the tighter the optimization; fluctuating loads require more flexible control strategies. Understanding daily and seasonal patterns makes all the difference in terms of avoiding oversizing versus underutilization.

Selecting Technologies without Making the System Too Complex

An efficient hybrid power solution would comprise a few different technologies working well together, rather than many that make just a slight difference. A solar setup combined with a battery storage and a traditional power generator can achieve most of the possible benefits.

There should be a rationalization of all additional technologies based only on improvement, and never based on mere capability.

Designing for Future Change Without Overbuilding

Future-proofing is often mentioned as a reason to oversize hybrid systems. While flexibility is useful, it could lock in unwanted capital expenditures.

A more beneficial method is modularity. The process of creating and designing systems that have expansion and reconfiguration abilities gives an organization the flexibility to cope with evolving demands without paying for unused capabilities at the initial stage. This method currently favors trends in hybrid power studies involving scalable designs rather than rigid ones.

Operational Reality Determines Long-Term Success

It can be seen that hybrid power generation schemes are more than just the point of delivery. Monitoring and understanding are important in realizing potential benefits.

Operating modes, automatic reactions to abnormal situations, and information about performance ensure that the hybrid power system remains on target regarding its goals even under real operating conditions.

Conclusion: Choosing Hybrid Power as a System Decision

Choosing a hybrid power solution is ultimately a system design decision. It is generally true that in the most successful projects, initial goals, expectations, and a recognition that implementation, integration, and control are just as important as hardware exist.

Hybrid power works best when complexity is deliberate, not accidental. By focusing on outcomes rather than components, organizations can choose hybrid power systems that deliver meaningful cost savings, improved resilience, and long-term operational confidence.